Which is more “environmentally friendly”: A paper or a plastic bag? A soda in an aluminum can, a styrofoam cup, or a corn-based cup?

The answers may seem obvious (the paper and can, right?) but the truth is actually quite murky. Are you talking about how much fossil-fuel-based energy it took to produce, transport, and dispose of the material? How much greenhouse gas that cup will generate in a landfill? Do you have access to commercial composting facilities?

Disposables are one of the most complicated areas of sustainability. The one simple rule to remember is that choosing reusable plates, utensils, and cups instead of the kinds intended for a single use (whether you recycle, compost, or trash them) is always a better choice.

Here are just some of the reasons why.

Which bin you toss it in matters. Correctly sorting compostable, recyclable, and other disposable products into proper bins is confusing for everyone, not just at Bon Appétit cafés. When the wrong items end up in the wrong bins (such as a transparent, corn-based cup in the recycling bin), that’s called “contamination.” (Bioplastics are compostable under certain conditions, but never recyclable — they just gum up the machines.) If a certain level of contamination in a load is exceeded, compost and recycling companies must divert all contents directly to the landfill, negating the energy and resources (including money, of course) that went into producing and obtaining these products. Waste-stream contamination has become responsible for enormous ecological damage.

We have implemented food waste reduction programs in all of our locations. A big part of that is composting kitchen food scraps. Unlike with our guests’ lunch leftovers, we can be sure that what we are sending to the municipal composting facility or the campus farm’s compost bins is just good-for-the-soil organic material.

Why bioplastics aren’t the answer (yet): Commodity crops such as soy and corn — the main plants from which “plant-based products” are made — are not benign products. Enormous amounts of fossil fuels are used to fertilize these crops, to power the manufacturing facilities where the products are made, to power the vehicles that transport the plants from the fields and the products from the manufacturer to warehouses, and in the manufacture of the packaging for the products themselves. And that’s not all: Fossil fuel-based fertilizers and the carcinogenic herbicide atrazine (banned throughout the European Union) are applied to more than 70% of the U.S. corn crop, and have many documented environmental side effects.

Another problem: While most bioplastics manufacturers tout them as “compostable,” they only break down in those composting facilities that employ very high heat. The campus farm’s compost pile does not. They are not recyclable, so most will end up in the landfill, where unlike plastic, they will biodegrade. And while that might sound good; actually, it’s not. Plant-based resins, like other organic material in a landfill, cause methane emissions. Methane is a greenhouse gas that is 25 times more powerful than carbon dioxide and contributing to climate change at an accelerated rate.

What Bon Appétit is doing

Disposables policy:

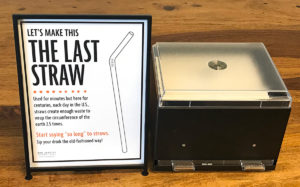

Where did all the straws go? Used once then discarded, plastic straws are the tip of the single-use-plastic iceberg clogging landfills, waterways, and oceans and poisoning wildlife. It’s estimated that Americans use 500 million plastic straws every day, very few of which are even recyclable. On April 18, 2018, one of Bon Appétit’s higher-education clients, the University of Portland in Portland, OR, became the first U.S. university to ban plastic straws at all food or beverage outlets on campus. On May 31, 2018, Bon Appétit announced that we are phasing out plastic straws and stirrers companywide, in our 1,000 cafés and restaurants in 33 states, starting immediately and to be completed by September 2019. Bon Appétit is the first food service company — or major restaurant company — to make this commitment in the country. We will offer non-plastic alternatives by request to guests with a disability or who just really think they need a straw.

Our first choice is to buy reusables (and attempt to limit the use of disposables for actual “to go” options only — more about that below). Where disposables are used, we opt first for those made with post-consumer recycled fibers, then that are recyclable, and then compostable if we have a closed-loop system with little chance of contamination. We set a goal for usage and monitor results on a monthly basis with the whole staff. We have routinely achieved 10% reductions as a result of careful monitoring.

In some locations, we have introduced eco-clamshells: a hard plastic clamshell that can be used many times and go through our dishwashing process to be sterilized. Guests exchange a token or pay a deposit when their food to go in one of these.

Waste stream helpers: The benefits of offering compostable or recyclable to-go ware are negated if those items get tossed into the regular trash. We provide clear signage at our waste sorting stations of what should go where. And since even with that signage, we’ve found high levels of contamination, we often team up with campus environmental groups to provide volunteer “sorting helpers” who help guide guests’ garbage to the right bin.

For here or to go? As much as we’d like for everyone to sit down and eat a leisurely meal with us, we understand that sometimes our guests are in a rush and can’t eat in the café. But we admit, it does disappoint us when guests choose to-go ware instead of china to eat in the café, then toss it on their way out. It’s a waste of natural resources and money, and our food doesn’t get a chance to shine! Hoping to discourage this practice, we periodically offer education about the disposables dilemma, in which we might create a visual display of the amount of to-go boxes used in one location in one week.

Learn more

NatureWorks: Food Composting Facilities Across The United States

EPA: Composting Where You Live

Sustainable Packaging – Myth or Reality — UK report